Global debt recently reached a milestone. If you add up the debts of all countries on the planet, you reach a staggering $91 trillion. More than a third of that figure comes from one country alone: the United States.

The country’s accumulated gross debt has reached $35 trillion, a figure so large that the International Monetary Fund warns that it is putting the entire world economy at risk.

But it’s hard to even imagine what the number 35 trillion looks like, let alone 91 trillion. So I decided to employ a time-honored journalistic device: break down the number so it’s easier to visualize.

Let’s say you have 35 trillion dollar bills and you lay them out side by side, starting with the Earth. How far would they go? To the Moon, for example?

It turns out that the moon isn’t even close. It only takes about 2.5 billion dollars to get to the moon. No wonder the IMF is worried: American debt has dared to go where no human has gone before.

“Yes, these are big numbers,” said Peter Blair Henry, an economist at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution. To get a sense of how big they are, Blair Henry agreed to join us as we followed our dollar bill into the solar system.

Let’s call it “the debt journey.” Our $35 trillion debt is so massive that our dollar trail would fly past Mars, which is 225 million kilometers away (about 1.5 trillion dollar bills). The next planet on the list is Jupiter, the giant of the solar system. But not giant enough (it takes about 4.5 trillion dollar bills to get to Jupiter). Next is Saturn. But at a mere 9 trillion dollar bills away, on average, not even Saturn can put a ring on the American debt.

We continue on to the outer planets. We pass Uranus and arrive at Neptune. Neptune is just under 30 trillion dollar bills away. We have reached the last official planet in our solar system and we still have about 6 trillion dollars of debt to pay off.

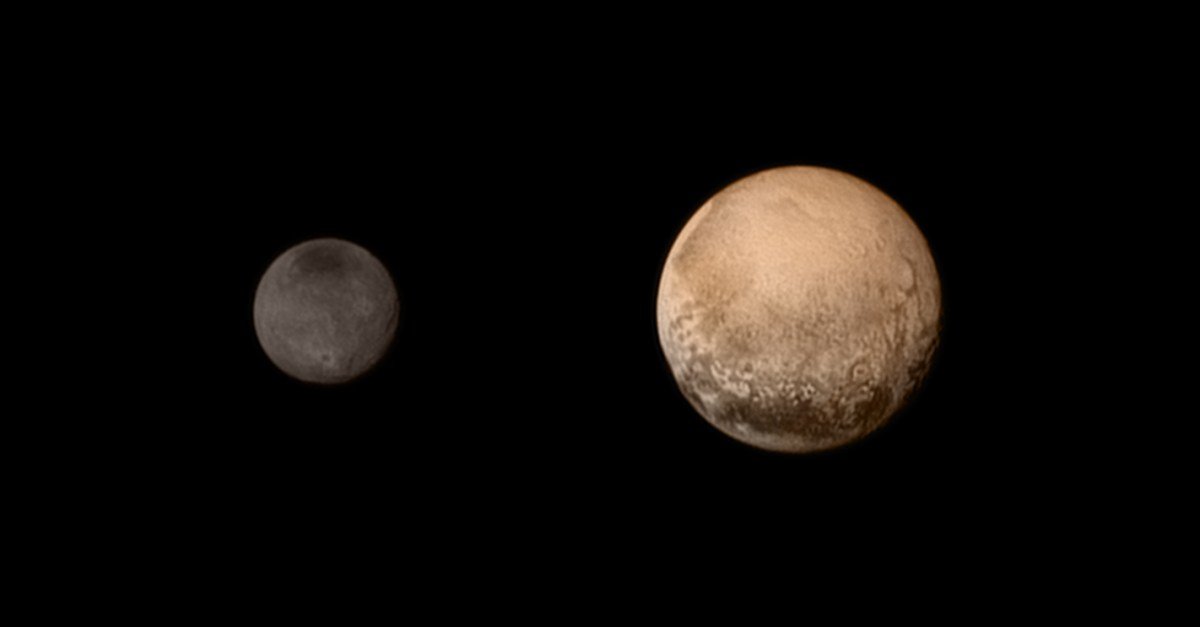

Keep in mind that a dollar bill is just over 15 centimeters long, and 35 trillion of them would almost reach Pluto. I did the math over and over again because I was actually stunned: no phasers were needed.

“Honestly, the best way to approach numbers as big as that is to think about ratios,” Blair Henry said. “What really matters is: how big is the debt relative to the size of the economy?”

In other words, the US debt, which is roughly the same as Pluto’s, is not a problem as long as the US is generating money roughly the same as Pluto. The problem is that this is not the case: the US is only generating money equal to that of Neptune.

Our economy is producing about $30 trillion worth of goods this year, measured in terms of gross domestic product. And our debt, which has been accumulating for decades, is $35 trillion. Right now, our debt-to-GDP ratio is about 120%. We owe more than we earn: that’s what Blair Henry is worried about.

“As your debt ratio increases, your finances become more and more difficult,” he said. “And the danger is that at some point your creditors will look at your debt situation and say, ‘Oh my God, you’re not going to be able to pay me.’”

So those creditors will start demanding higher interest rates when they lend money.

“Borrowing costs are rising dramatically and that could lead to a financial crisis,” Blair Henry said.

In fact, that has already begun to happen. In the United States, borrowing costs were really low for a long time. The government could borrow money practically for free because people trusted the country to pay it back. The size of the debt didn’t seem to matter.

But as that debt has soared, lenders have begun demanding higher interest rates from the United States. “We’ve reached a tipping point,” said Harvard economist Kenneth Rogoff. “At least I think so.”

Rogoff was chief economist at the International Monetary Fund for years and sees rising interest rates on our debt as a huge economic problem.

“This is the biggest thing that’s happened in the world economy in the last five or 10 years,” he said. That’s because the US has debt practically the size of Pluto, so even a small increase in interest rates becomes galactic very quickly.

“The interest payments we have to make on American debt have skyrocketed,” he added. “I think the interest payments alone are equivalent to our military budget.”

This year, the interest bill is expected to approach $1 trillion. That’s a trillion dollars that we can’t spend on, say, roads, health care, or growing the economy. Our debt is not only large, it’s draining our resources.

“People had this idea that it was free, that you didn’t have to worry about debt,” Rogoff said. “That’s the big change that’s happened in the world, it’s just thrown a bucket of cold water on the idea that debt doesn’t matter.”

Rogoff said that if another global crisis, like COVID, occurs and the U.S. needs to spend a lot of money quickly, borrowing could become even more expensive. That becomes risky, potentially even destabilizing the economy. And no one could step in to save the day because almost every other major economy is also intragalactically in debt.

Rogoff said debt is a great tool, but it should not be a free-for-all. “It’s convenient to use debt for tough times, but you shouldn’t declare every day a tough day.”

On Neptune, it apparently rains diamonds. But until we can get them, getting the debt under control isn’t that complicated, Rogoff said. It would require Congress to make some tough decisions: cutting spending and raising taxes. We’d have to tighten our belts as a country, and Congress would have to compromise.

Perhaps it would be more realistic to look at those diamonds on Neptune.

There’s a lot going on in the world. Marketplace is here to help you through it all.

You rely on Marketplace to analyze world events and tell you how they affect you in a factual and accessible way. We depend on your financial support to continue making this possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism you trust. For just $5 a month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can continue reporting on the things you care about.

#debt #hit #trillion #putting #global #economy #risk #Marketplace